Summary of Useful Links on this Topic:

- Essential Vocabulary: Quizlet

- BBC Bite Size History: The Black Death from www.bbc.co.uk

- The Plague in Sydney, 1900: A Picture Gallery

- The Black Death and Early Public Health Measures from www.sciencemuseum.org.uk

- Death Defined: Black Death – Causes and Symptoms from http://historymedren.about.com/

- How the Black Death Worked from www.howstuffworks.com

- A General Account, including Boccaccio’s Description of the Plague’s Symptoms from http://www.eyewitnesstohistory.com/

- Global Impacts of the Black Death from www.abouteducation.com

- Decoding the Black Death through Archaeology from www.sciencedaily.com

Dear S2Y,

The Black Death would take a heavy toll on any society that lacked modern medicines, hygienic living conditions and well-stocked hospitals. For instance, only 22 years ago, there was an outbreak of pneumonic plague in India, which led to widespread panic, attempts by the government to stop mass evacuations from slum areas and ultimately hundreds of deaths. Journalists entering the area took their own antibiotics with them – a wise move! You can read a New York Times report about this outbreak here.

In 1900, 303 people in Sydney caught the bubonic plague and 103 died. Although modern antibiotics were not available in 1900, scientists knew by then how the disease was spread. This allowed the authorities to take appropriate measures to combat the disaster, such as appointing rat-catchers and fumigating the slum dwellings in the Rocks. A bounty was placed on rats – sixpence per rat according to one Melbourne report. Poor and unemployed men became professional rat catchers. You can see pictures of the crisis in Sydney below.

The situation in medieval Europe when the plague struck was exacerbated by ignorance, superstition, atrocious living conditions and poor medical practice. At the time, no one knew the cause of the disease or suspected the existence of bacteria. Many falsely assumed that the disease was caused by the movements of heavenly bodies or infected air. There was also a pervasive belief that the plague was God’s punishment for sin. The reactions of most people were characterised by superstition and panic, as well as a lack of systematic observation and evidence-based medical practice. Finally, the unhygienic living conditions provided the ideal environment for rats, fleas and indeed infections of all kinds.

I hope you find this topic as gruesome, heart-rending and captivating as I have always found it.

– Ms Green

The Black Death in Sydney and Melbourne, 1900

Here is a picture of the rat-catchers at work:

Copyright:State of NSW. Kindly provided by the State Records Authority of NSW. That pile in the middle is dead rats.

♦Go to this link to view other fascinating and gruesome pictures, including closeups of rat heaps, quarantine areas being demolished, etc:

LINK: http://gallery.records.nsw.gov.au/index.php/galleries/purging-pestilence-plague/

♦Marvellous Melbourne (or Smellbourne as one wag of the period called it) also suffered from a case of the disease; read about a case in Camberwell at the link below:

LINK: Plague in Camberwell

The Black Death in Medieval Europe

One-third of the people of Europe died from this disease – and that is only counting the first time it struck. In 1348 the population had no immunity at all. In the same way, the native populations of South America and Australia had no immunity to smallpox, which helps to explain why smallpox wiped out a substantial percentage of these populations. The plague returned at regular intervals over the next 350 years in Europe. It was always devastating, but it did not kill as many people as in 1348 and 1349.

The situation in medieval Europe made people particularly vulnerable to such a disease:

Sanitation: General hygiene was very poor. People didn’t know about bacteria and as they walked along streets they had to step over faeces. The cities stank. Rats had plenty to feed on thanks to the butchers working in public and leaving piles of offal on the streets. Fleas were also commonplace. Peasants expected to have fleas.

Sanitation: General hygiene was very poor. People didn’t know about bacteria and as they walked along streets they had to step over faeces. The cities stank. Rats had plenty to feed on thanks to the butchers working in public and leaving piles of offal on the streets. Fleas were also commonplace. Peasants expected to have fleas.

Widespread Poverty: There was a great deal of poverty, malnutrition and poor health in a large percentage of the population. The Black Death therefore struck an already weakened population.The rate of mortality in untreated cases is reportedly around 40–60%. Presumably a healthy, well-fed person would have a better chance of surviving than a poor, malnourished peasant – and Europe’s population was largely made up of poor, malnourished peasants.

Widespread Poverty: There was a great deal of poverty, malnutrition and poor health in a large percentage of the population. The Black Death therefore struck an already weakened population.The rate of mortality in untreated cases is reportedly around 40–60%. Presumably a healthy, well-fed person would have a better chance of surviving than a poor, malnourished peasant – and Europe’s population was largely made up of poor, malnourished peasants.

|

The medieval life expectancy According to a book from our school library, “The Death” by Amanda Braxton-Smith, some historians believe, based on evidence from digs in Ireland, that the average lifespan in the Middle Ages could have been about 25 years. This evidence suggests that over half the women were dead by the age of 35 and one-third of the population had died before the age of 14. Of course, this may not be true of Europe as a whole but it gives an insight into medieval life (and death). |

♦To read about the mortality rate of the plague, go to the link below. You should be aware that just to complicate matters there were three kinds of plague, and the prognosis (likely medical outcome) for each was different.

LINK: Details of the plague’s mortality rate (with extra information about rats, fleas and so forth)

Medical Knowledge in Christian Europe: Medical knowledge, at least amongst Christians, was almost non-existent. While Islamic physicians were quite scientific in their methods, Christian doctors were ignorant of anatomy and did not use a scientific method in their treatments. The Roman Church was partly to blame. It controlled what doctors learned and it prohibited the dissection of bodies. This meant that in one French medical school, for instance, there was only one practical anatomy lesson in two years. An abdomen was opened and inspected; that was all. The prescriptions of doctors at the time of the plague were dangerous rather than therapeutic.

Medical Knowledge in Christian Europe: Medical knowledge, at least amongst Christians, was almost non-existent. While Islamic physicians were quite scientific in their methods, Christian doctors were ignorant of anatomy and did not use a scientific method in their treatments. The Roman Church was partly to blame. It controlled what doctors learned and it prohibited the dissection of bodies. This meant that in one French medical school, for instance, there was only one practical anatomy lesson in two years. An abdomen was opened and inspected; that was all. The prescriptions of doctors at the time of the plague were dangerous rather than therapeutic.

The Church: Another problem was that the Church viewed disease as a punishment for sin. Some people believed that leprosy could be brought on by too much lust. In such an environment, careful scientific examination and rigorous observation of symptoms would be uncommon.

The Church: Another problem was that the Church viewed disease as a punishment for sin. Some people believed that leprosy could be brought on by too much lust. In such an environment, careful scientific examination and rigorous observation of symptoms would be uncommon.

Ignorance and Superstition: If doctors were ignorant, then the rest of the population, mostly illiterate, was even more so. Wild rumours and prejudices rapidly took hold. This meant that instead of doing useful things like quarantining people, cleaning up filthy areas and burning plague-infested areas – all measures taken by the Sydney administration in 1900 – medieval people often reacted by blaming the innocent.

Ignorance and Superstition: If doctors were ignorant, then the rest of the population, mostly illiterate, was even more so. Wild rumours and prejudices rapidly took hold. This meant that instead of doing useful things like quarantining people, cleaning up filthy areas and burning plague-infested areas – all measures taken by the Sydney administration in 1900 – medieval people often reacted by blaming the innocent.

From Wikipedia Commons, originally from the Jewish Encyclopedia, 1901–1906, and now in the Public Domain; picture titled, “French Jews of the Middle Ages”

Persecution of Jewish People: The Jews were one group who were accused of poisoning wells and infecting people with plague.

Historians have suggested this might have been connected with the fact that fewer Jews died from the plague. The Jewish holy book (Torah) gives advice on basic hygiene to stop the spread of diseases. This meant many Jews refused to use the unhygienic wells (located near the town sewage pit), choosing instead to drink from fresh water sources.

This may have caused superstitious and ignorant people to blame the Jews for the plague. Consequently Jews were massacred, tortured and even burned alive. It was horrific. Some writers believe it was the worst persecution of the Jews before the 20th century, when the Nazis, with all the technology of the modern world behind them, committed atrocities against the Jewish population of Europe.

A massacre of a specific minority is sometimes called a pogrom.

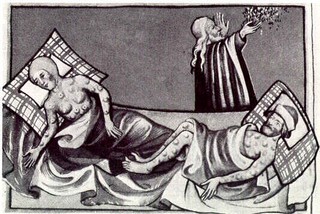

Picture in Public Domain from Wikimedia Commons. Check the buboes. The man in the background may be holding a bunch of herbs, which were erroneously believed to help ward off disease by filling the air or at least the person’s breathing space with healthy odours.

|

“Woe is me of the shilling in the arm-pit; it is seething, terrible, wherever it may come, a head that gives pain and causes a loud cry, a burden carried under the arms, a painful angry knob…” – Jeuan Gethin (died 1349) – quoted in “The Death” by Amanda Braxton-Smith. |

Medieval Recommendations for the Plague

People should seclude themselves from others and stay away from the infected air.

People should seclude themselves from others and stay away from the infected air.

People should burn scented woods to purify the bad air and fill their homes with pleasant-smelling plants and flowers.

People should burn scented woods to purify the bad air and fill their homes with pleasant-smelling plants and flowers.

Try to remain tranquil.

Try to remain tranquil.

Open and cauterize the buboes (burn them with a hot iron or caustic agent) and apply some substance to draw out the poison. One recipe for such a substance was a plaster made from gum resin, roots of white lilies and dried human excrement.

Open and cauterize the buboes (burn them with a hot iron or caustic agent) and apply some substance to draw out the poison. One recipe for such a substance was a plaster made from gum resin, roots of white lilies and dried human excrement.

Take soothing potions. One recipe for a potion was: take an ounce (28 grams) of gold, 11 ounces of quicksilver, dissolve and let the quicksilver escape; add 47 ounces of water and drink. Fortunately few people would have had the wealth or resources to make such a potion.

Take soothing potions. One recipe for a potion was: take an ounce (28 grams) of gold, 11 ounces of quicksilver, dissolve and let the quicksilver escape; add 47 ounces of water and drink. Fortunately few people would have had the wealth or resources to make such a potion.

Some doctors suggested people should bathe in urine. Others warned against bathing as it would open the pores to let in the disease.

Some doctors suggested people should bathe in urine. Others warned against bathing as it would open the pores to let in the disease.

Some people thought the plague could be avoided by sniffing bad smells such as latrines (a hole in the ground used as a toilet). Following the theory that the two bad smells worked against each another, some people put dead animals in their houses.

Some people thought the plague could be avoided by sniffing bad smells such as latrines (a hole in the ground used as a toilet). Following the theory that the two bad smells worked against each another, some people put dead animals in their houses.