![]() Dear S2Y,

Dear S2Y,

As a historian and discerning writer, you need to choose precise words.

Here are some imprecise words that one hears every day: “awesome”, “amazing”, “extraordinary”, “wonderful”, “good”, “marvellous”, “terrible”, “bad” – and so on. In speech, such words are easy to use, even though they sometimes fail to convey exact meanings. I’m not saying that you should never use them. Just be sparing with them.

In writing, some of the words below might allow you to express finer shades of meaning and capture the nuances of human experience. That’s what words are for. Choosing an exact word or phrase is a deliberate mental act that will allow you to express yourself with conviction and even formulate ideas in a more rigorous way. Weigh your words as you choose them. In this way you will become a memorable writer, not a pedestrian one.

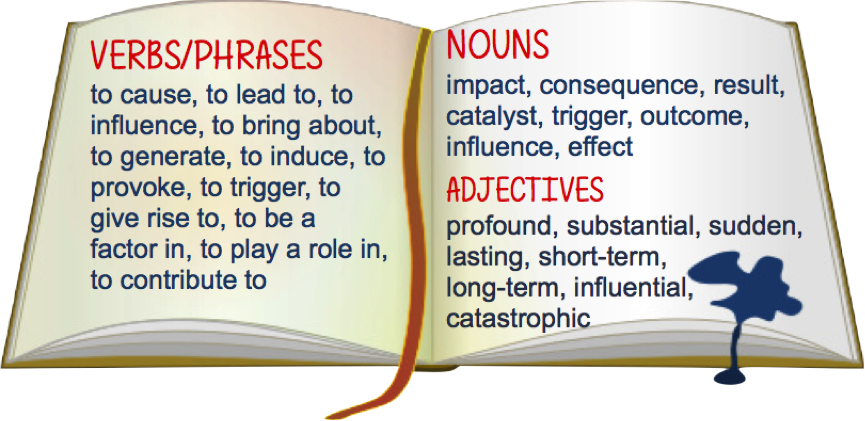

| Positive words for describing the life and legacy of people in history – for describing admirable actions and characteristics | Negative words for describing the life and legacy of people in history – for describing people or actions that you deplore or condemn |

| influential, determined, resolute, purposeful, tenacious, brave, courageous, astute, quick-witted, insightful, discerning, far-sighted, ingenious, unconventional, visionary, forward-thinking, enlightened, inventive, innovative, industrious | unwise, thoughtless, inhumane, ruthless, callous, cowardly, hasty, immoral, misguided, ill-judged, senseless, cruel, ill-considered, foolish, mistaken, dangerous, imprudent, irresponsible |

For those of you who were present to watch the BBC documentary, “Blood of the Vikings”, you may recall hearing Charlemagne’s name. The commentators mentioned that his military campaigns and slaughters of so-called pagans were possible factors in the Vikings’ increasingly violent raids, which began in the late eighth century. At just that time, Charlemagne was establishing what came to be known as the “Holy Roman Empire”. “Establishing” is such a clean, neat word, but in reality Charlemagne conducted many military campaigns that were far from gentle, orderly and merciful; his “establishment” of his empire entailed a great deal of force and bloodshed. In a sense, the word “establishment” here is rather euphemistic, just like the phrase “surgical bombing” as it was employed during the Iraq War.

While many accounts of Charlemagne present him in a glowing light as the father and founder of European culture, some historians view him as a brutal warlord. Which of these extremes is most clearly supported by the evidence? Can one argue that he somehow combined some elements of both extremes? Which view would you support more?

In reality, of course, all historical characters are likely to have positive and negative sides, although the preponderance of violent, murderous dictators in the twentieth century sometimes makes it difficult to maintain one’s faith in human character…

Your task is to decide what kind of man Charlemagne was and describe him in all his complexity and contradictions.

Charlemagne set up a significant and powerful empire and was influential in the development of Europe.

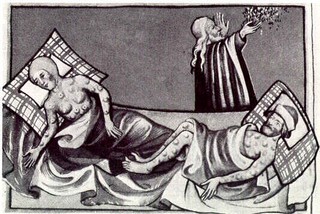

Even though Charlemagne is remembered for his contributions to law, justice and education, he sometimes took harsh measures against those who resisted his power. For instance, he forced people to be baptised as Christians and executed thousands of Saxon prisoners in one day.

So on the one hand, Charlemagne encouraged learning and admired scholars. On the other, he was prepared to act viciously to strengthen and consolidate his power.

[wmd-divider style=”knot” spacing=”40″ color=”#002426″ size=”2″ ls-id=”55dec35d93d68″/]

Find out more by reading the websites below.

♦Then create a word document in which you write a careful, considered paragraph (or two) on the life, character and legacy of Charlemagne. Ensure that you include answers to these questions:

- What do you admire about him?

- Which actions, if any, would you criticise? Use the words in the table provided above.

- Show me your paragraph during our next class, before adding it as a comment to this blog post.

- You may choose to select, instead of Charlemagne, one of the other people listed on pages 256-8 of your text: Leif Ericson, Suleiman the Magnificent or Galileo Galilei.

I chose Charlemagne for this task because of the complexity of his moral character, but I am willing to concede that each of these other characters is worthy of your mature contemplation.

Here are some recommended websites:

- http://www.lucidcafe.com/library/96apr/charlemagne.html

- http://www.historyforkids.org/learn/medieval/history/earlymiddle/charlemagne.htm

- http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/charlemagne.shtml

- http://historymedren.about.com/od/charlemagnestudyguide/p/sg_biography.htm

- http://historymedren.about.com/od/charlemagnestudyguide/p/sg_people.htm

- http://www.findingdulcinea.com/features/profiles/c/charlemagne.html

- http://www.history.com/topics/charlemagne

[wmd-toggle tab_background=”#066196″ tab_color=”#fff” content_background=”#2196d1″ content_color=”#fff” border_radius=”4″ ls-id=”55dec48bf250d”][wmd-toggle-tab title=”A particularly critical description and a reconstructed portrait of Charlemagne”]%3Cp%3E%3Cspan%20style%3D%22font-size%3A%2012pt%3B%20color%3A%20%2399ccff%3B%22%3EA%20particularly%20critical%20description%20and%20a%20reconstructed%20portrait%20of%20Charlemagne%3C%2Fspan%3E%3C%2Fp%3E[/wmd-toggle-tab][/wmd-toggle]

http://www.reportret.info/gallery/charlemagne1.html

An overview of the history underlying Charlemagne’s rise to power, from the Khan Academy:

A brief account of the Carolingian Renaissance, with references to the darker side of Charlemagne’s character (from 8 minutes onwards):

|

[wmd-buttons style=”stiched” button_color=”#1279b5″ font_color=”#ffffff” size=”2″ border_radius=”4″ position=”center” target=”_self” ls-id=”55de99fdc7f3f”][wmd-buttons-button label=”Kahoot” link=”https://create.kahoot.it/?_ga=1.135484466.2077747923.1437027700#/preview/cd32a504-9e1d-4ec3-835d-020022c68445″/][/wmd-buttons] The Vikings Play alone in Preview Mode | Play with others in Class Mode To play alone, make an account here To play with others, teachers can click on Class Mode, while students can enter the game by inputting the game pin at kahoot.it.

|